Over the past year, the phrase “male loneliness epidemic” has been circulating with new urgency, as if it names a problem that has only just emerged. In reality, it is less a new condition than a recurring one, historically contained by marriage, hierarchy, and obligation, and only now surfacing openly as those structures lose their hold. What has changed is not male isolation itself, but the social landscape around it. Women now have far more latitude to opt out of relationships that demand emotional labor without reciprocity, and that shift has exposed a long-standing imbalance that was previously absorbed, quietly, by others.

Watching the world premiere of Eugene Onegin at San Francisco Ballet, it was impossible not to recognize this dynamic at work, rendered with 19th-century specificity and contemporary clarity. Long before the language of epidemics, Alexander Pushkin wrote a character who is handsome, culturally fluent, and deeply bored. Eugene Onegin is not deprived of love or opportunity. He rejects them, repeatedly, until rejection itself becomes his defining trait.

That story, staged now, lands with particular force.

San Francisco Ballet’s Eugene Onegin, which premiered Friday night at the War Memorial Opera House, arrives as a major new commission under Artistic Director Tamara Rojo, whose tenure has emphasized the necessity of creating new full-length works rather than relying solely on inherited repertory. A new ballet lives or dies in the present. It exposes the current state of a company, its dancers, and the assumptions it is willing to challenge.

Choreographed by Resident Choreographer Yuri Possokhov, Onegin is co-commissioned with Chicago’s Joffrey Ballet and built on Pushkin’s novel-in-verse. It is not a ballet about romance in the conventional sense. It is a ballet about refusal, about emotional immaturity mistaken for sophistication, and about the damage inflicted when detachment is treated as a virtue.

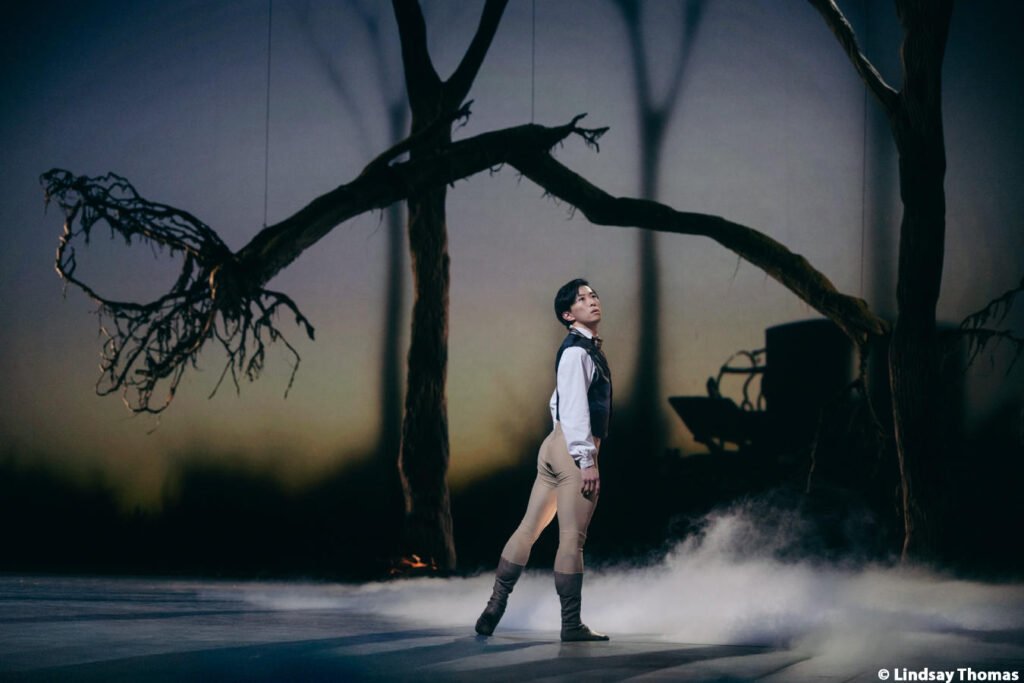

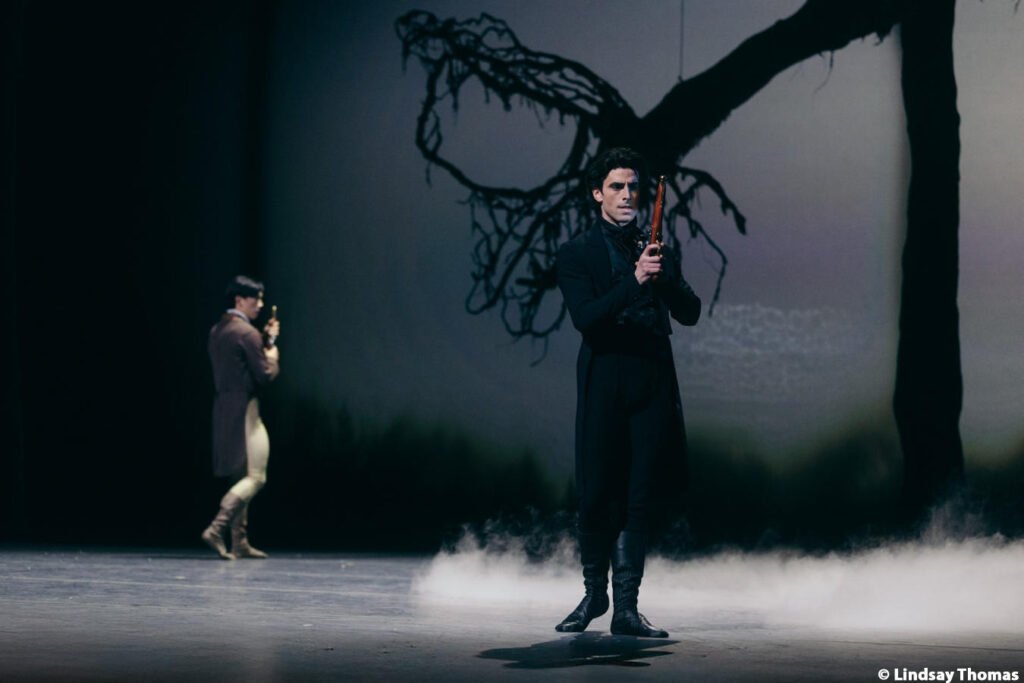

Possokhov embraces Pushkin’s poetic logic rather than sanding it down for narrative efficiency. The choreography leans into surrealism and dream structure, allowing inner states to take physical form. The changing seasons operate not as decorative interludes but as emotional architecture, with the corps de ballet functioning almost like fate itself, elegant and unsentimental. A fever-dream sequence populated by dancers in uncanny animal heads stands out as one of the work’s most striking passages, playful and unsettling in equal measure. It reads not as spectacle for its own sake, but as a psychological rupture, a glimpse into the interior chaos Onegin refuses to confront.

Composer Ilya Demutsky’s score is unabashedly cinematic, avoiding the gravitational pull of Tchaikovsky in favor of something more contemporary in pacing and texture. It retains classical rigor while adopting a modern sensibility, creating propulsion without sacrificing emotional nuance. The music does exactly what ballet music must do at its best. It leads, it listens, and it leaves room for breath. For a world premiere, it lands with remarkable confidence.

That cinematic quality is reinforced through the production’s use of projection and recorded text, including excerpts of Pushkin’s poetry as heard in the performance itself. Spoken language is rarely heard in classical ballet, and here it operates as texture rather than narration. The effect is immersive rather than instructional, layering visual and auditory stimuli without overwhelming the dancers at the center of the work.

Visually, Eugene Onegin is one of the most ravishing productions San Francisco Ballet has unveiled in recent years. Academy Award and BAFTA winner Tim Yip of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon fame designed the costumes, bringing a couture sensibility that reads instantly from any depth in the house. Fabrics are chosen not just for beauty but for movement and sound. Skirts carry weight and swish audibly through space. Colors shift under light. Status, youth, and emotional temperature are communicated through texture and hue as much as through choreography.

If you were struck by the Christian Lacroix-designed costumes in San Francisco Ballet’s run of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, you recognize the particular thrill of fashion thinking in motion. Yip’s approach is different but no less luxurious, drawing on late-19th-century Russian opulence with a slightly gothic edge, as though splendor itself is always one misstep away from decay. The ballroom scenes, particularly the grand waltzes, are visual feasts, and on opening night they were carried decisively by Jacey Gailliard, Pemberley Ann Olson, and Tyla Steinbach. All three were immediately legible from any depth in the house, with strong lines, open carriage, and a clarity of attack that anchored the large group choreography. Their elegance and control gave the waltz scenes their shape and momentum, turning what could have been decorative spectacle into something structurally coherent and genuinely exhilarating.

One of the most unexpectedly transporting elements of those scenes was auditory rather than visual. The ballet-length taffeta skirts, with complementary ombré tulle layers pillowing beneath, produced a soft, percussive swish as the dancers moved through the waltzes. It landed somewhere between fabric and rhythm, an accidental accompaniment to the orchestra. Swish, ba dum bum. Swish, ba dum dum. The sound rose and fell with each turn, catching just beneath the music and above the floor, impossible to unhear once it registered. It was a kind of couture ASMR, the byproduct of motion, weight, and impeccable timing, and days later it still replays in my mind, a tactile memory of how the ballroom scenes felt as much as how they looked.

The cast on opening night elevated the production from ambitious to possessed. Katherine Barkman, as Tatiana, anchored the evening with a performance of exceptional emotional clarity. Exactly one year earlier, she appeared on the cover of San Francisco Ballet’s program as Manon, and that proximity matters. Watching Barkman return to the same stage 365 days later in a radically different heroine underscored the breadth of her artistry and the trust the company places in her. Her movement has a fluid, almost buttery quality that makes difficult choreography appear effortless. More importantly, she brings dignity to vulnerability. Tatiana’s sincerity never reads as weakness. It reads as strength offered freely and, ultimately, refused.

Joseph Walsh’s Onegin was chilling precisely because it refused drama. He moved through the ballet with the assurance of someone accustomed to being watched and rarely required to respond. The dancing was pristine, but rarely emphatic. He seemed to pull energy inward rather than throw it outward, creating a sense of emotional remove that was impossible to miss. Walsh played Onegin as a man permanently buffered from consequence, someone who mistakes detachment for discernment and irony for intelligence. When love is offered, he treats it as a minor inconvenience. When friendship is damaged, he registers it too late to matter. There was no catharsis in his portrayal, no visible reckoning. Instead, there was an accumulating emptiness that followed him from scene to scene, until it became clear that this vacancy, not rage or grief, is the true engine of the tragedy.

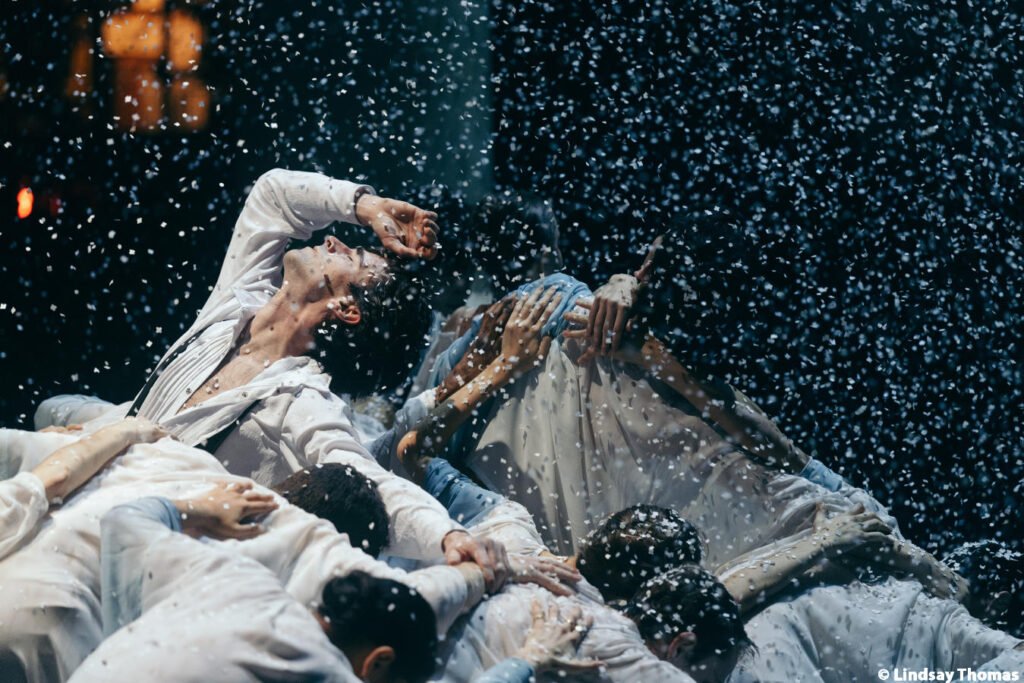

Wei Wang and Wona Park entered their first pas de deux already in motion, already committed, as if the choreography had begun before the audience was ready for it. Possokhov gives them material that refuses neutrality: lifts that tip past center, landings that demand instant recalibration, transitions that rely on velocity rather than preparation. The dancing was unapologetically excessive. It asked for strength, speed, and nerve in equal measure, and Wang and Park did not soften the choreography, letting its formidable difficulty register cleanly and without disguise.

That choice gave the duet its emotional force. This was not intimacy rendered gently, but connection tested under pressure, with difficulty functioning as the primary language of trust. Their movement carried the intensity of young love experienced at full volume, before caution intrudes. Nothing was smoothed, nothing softened. By the time the duet resolved, the audience had already been shown exactly how much there was to lose.

At curtain call, their pause and embrace felt like decompression. Not triumph, not performance, but the quiet recognition of having come through something exacting together. Those moments linger because they cannot be staged. They resonate because the body remembers what it has just done.

Possokhov also gives the corps de ballet, particularly the younger male dancers, unusually substantial material. A summer-season sequence featuring an extended ensemble of cavaliers stood out for its athleticism and musicality. A stage filled entirely with men dancing together, given time and space to develop, is a rare pleasure, and here it was both generous and thrilling.

What ultimately gives Eugene Onegin its contemporary charge is not its updating of Pushkin but its refusal to soften him. Onegin is not punished because he is misunderstood, he is punished because he consistently mistakes detachment for discernment and freedom for depth. He rejects love, betrays friendship, and only confronts loss when there is no one left willing to absorb his indifference.

In that sense, the ballet offers a clear-eyed reading of a character type that continues to recur. Emotional immaturity paired with entitlement does not disappear when named. It simply becomes harder to ignore. Possokhov’s Onegin understands that truth, and trusts the audience to sit with it.

Late in the ballet, this poetry passage arrives quietly, briefly shifting the frame without offering resolution, as Pushkin’s words appear in San Francisco Ballet’s staging:

Alas our youth was what we made it

Something to fritter and to burn

When hourly we ourselves betrayed it

And it deceived us in return

When our sublimest aspiration

And all our freshest imagination

Swiftly decayed beyond recall

Like foliage rotting in the fall

Eugene Onegin runs at the War Memorial Opera House through February 1, 2026.