“Ballet is where we find our center,” said Rita Moreno from the stage on opening night. As the evening’s honorary chair, her presence alone carried weight, but the line itself landed with unusual stillness. It arrived quietly, without theatrics, and stayed with me.

One of the advantages of writing for a national audience while living in San Francisco is time. There is space to resist the pressure of immediacy, to let an experience settle before translating it into language. That matters with an event like the San Francisco Ballet Opening Night Gala, which compresses spectacle, labor, money, politics, and beauty into a single evening that moves faster than it can be fully absorbed.

We arrived on the front steps of City Hall on a deep sapphire blue carpet, the color repeating itself throughout the night like a visual refrain. Guests paused instinctively on the stairs, adjusting posture, smoothing gowns, waiting their turn for photos before being ushered inside. It is a familiar ritual, but one that still carries weight; a night that temporarily rearranges the city’s attention, polished, highly choreographed, and unmistakably deliberate.

Inside, champagne flowed beneath the rotunda as voices layered over one another, the scale of City Hall both swallowing and amplifying conversation. There was food, there were greetings, and there was that brief suspended moment before the night accelerates, when everyone seems to take a collective breath and register where they are.

This was my fourth gala, my fourth season moving through the orbit of donors, patrons, watchers, and the watched. The evening passes too quickly to fully register while you are still inside it, which is perhaps part of its design.

Objectively, this year came with proof. This year, the numbers told the story.

Following a historic Nutcracker season that grossed more money than any other in the company’s history, the gala exceeded previous fundraising records and sold out completely, waitlist included. City Hall was packed in a way I had never seen for the Ballet before. The density of bodies alone made the success visible before anyone mentioned figures. In a year that has felt precarious for arts institutions across San Francisco, the Ballet, at least on this night, was clearly thriving.

The performance itself was more complicated, and more considered, than early chatter suggested.

Taken as a whole, the program revealed something instructive about the company under Tamara Rojo as she enters her third season. Rather than attempting to modernize the gala through overt messaging or surface-level gestures, Rojo structured the evening around contrast. She allowed the finale to absorb the spectacle so that everything preceding it could move in the opposite direction.

What came before the finale was a sustained argument for restraint. Clean lines. Minimal sets. Low bravado. Dance for dancers’ sake. These were works that did not rely on sparkle, scale, or excess to justify themselves. What remained was the movement, the bodies, the relationships between dancers and audience. Taken together, the program suggested that Rojo understood exactly how cheesy the finale might read, and instead chose to surround it with something quieter, more intellectual, and more future-facing.

Jasmine Jimson opened the night with Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of Isadora Duncan, danced with a grand piano fully onstage beside her. The piano shared the space with her rather than disappearing into accompaniment. In keeping with the Duncan tradition, the movement rejected ornamental classicism in favor of breath, musicality, and emotional clarity. Jimson danced as if the body were thinking in real time, loose and expressive, prioritizing feeling over display. At moments she worked with a long scarf, moving it rhythmically as an extension of phrasing, and later released a large handful of flower petals into the air with theatrical restraint. There was no set, no ensemble, no visual excess. The choice to begin the gala this way felt deliberate and intellectual, an invocation of modern dance history as a corrective to spectacle.

Madeline Wu followed with the Act III pas de deux from Don Quixote, and the shift in energy was immediate. This was my first time seeing the company’s new principal dancer take on a canonical showpiece at full scale, and she met it with confidence. Wu arrived from overseas, where she most recently danced with Stockholm’s Royal Swedish Ballet, bringing with her a polish that registered instantly.

Don Quixote is fast, demanding, and merciless. Wu flirted with the music and choreography, punctuating phrases with mischievous smiles and sassy flicks of her wrist. Her jumps were expansive, her turns decisive, her extensions long but purposeful. The technique was classical, but the sensibility was not reverential. She danced as if tradition were a foundation rather than a constraint. In a company long associated with heritage, her presence felt like a clear argument for evolution without apology.

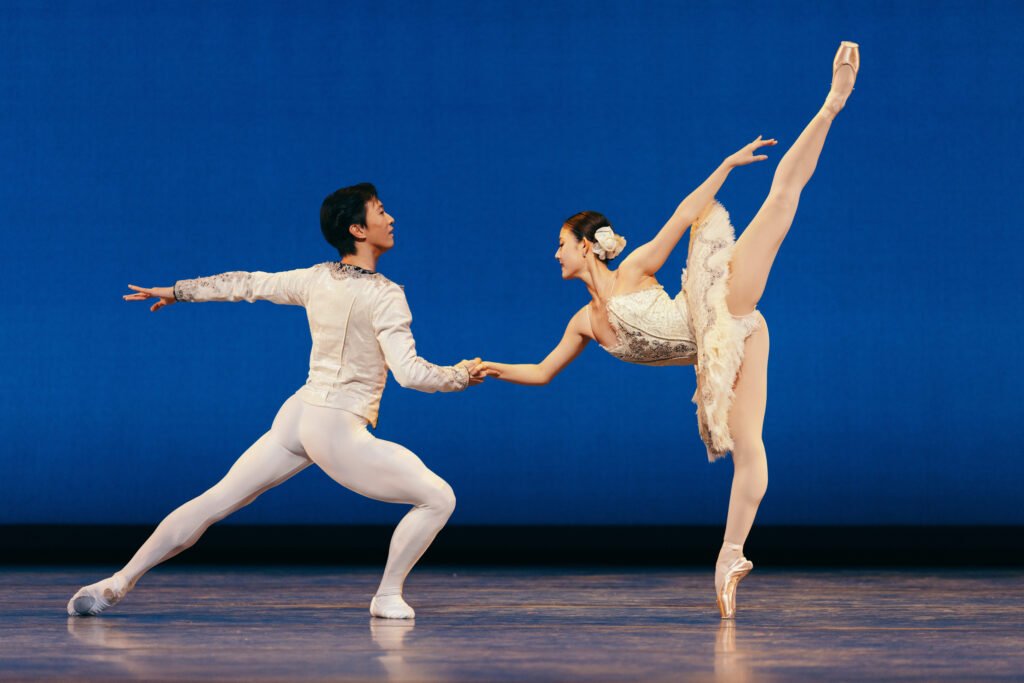

That restraint made the return to classical form feel intentional rather than nostalgic. The Grand Pas Classique, danced by Wei Wang and Wona Park, is, hands down, the strongest principal pairing in the company. I am always delighted to see them together. There is an ease and mutual intelligence between them that recalls elite Olympic figure skating pairs, where timing, trust, and shared instinct are everything.

This is classical ballet distilled to its essentials: speed, control, musicality, and absolute partnership. Park’s footwork was razor-sharp, buoyant without tipping into excess, while Wang matched her with effortless elevation and unforced authority. Watching them, I was reminded of the MGM era of ballet on film, when choreography trusted clarity, precision, and partnership to carry the frame. When I asked my photographer, Chloe, which performance stayed with her most from the night, this was the one she named without hesitation. The pas de deux read as proof of how thrilling classical technique can be when performed at this level.

We have seen Sasha DeSola as everything epic. As Odette and Odile. As Cinderella. As Giselle. As the Sugar Plum Fairy. Here, in “Forever” from William Forsythe’s Blake Works I, danced with Max Cauthorn, she appeared stripped down to essentials: a leotard, a wrap skirt, a bare stage. The duet felt like peeking into an intimate studio rehearsal, the kind you might glimpse at ballet school if you lingered in the hallway and caught one of the “big girls” quietly working something out. Forsythe’s choreography exposed structure rather than hiding it. There was no insulation. What remained was discipline, listening, and trust.

Adji Sissoko appeared in the epilogue pas de deux from Deep River, choreographed by Alonzo King, performed with Harrison James, and for me it was the most meaningful moment of the evening. One of the reasons I return to this gala is its openness to collaboration with adjacent dance communities, and here that openness felt essential rather than ornamental.

Sissoko, a principal dancer with Alonzo King LINES Ballet, brought a different physical vocabulary onto the War Memorial stage. At 5’10”, she moved with the power and elasticity of a track star, her extensions seeming to slice through space. Set to music by Jason Moran, the piece demanded grounded strength and emotional density. Watching two companies share a stage, trade audiences, and dissolve institutional boundaries, even briefly, felt significant. In a moment when resources are scarce, collaboration reads further than mere a gesture, and more clearly as an act of survival.

The finale was led by Nikisha Fogo and Cavan Conley, with Fogo fresh off her New Year’s Eve wedding in Mexico City. When I say these dancers are the true royalty of San Francisco, I mean it sincerely. I am more interested in what they are doing, where they are traveling, and what they are wearing than I am in most celebrities or socialites in the room. Their lives are compelling to witness, because they are earned through discipline.

Fogo and Conley closed the performance with a confidence that felt grounded and assured. There was joy in it, yes, but also stamina, professionalism, and generosity toward the audience. Ballet dancers live inside an intensity most people never see. They rehearse relentlessly, perform through injury, and give the best years of their bodies to an art form that offers little protection and no guarantees.

If anything in this country still deserves to be called American, it is these dancers. The ones who grow up spending more hours in dance studios than classrooms. The ones who learn choreography at speed, perform through injury, and show up night after night with their hair done, their shoes broken in, their bodies pushed to the edge of what they can take. They adapt to whatever is asked of them, whether it is forty performances of The Nutcracker, a character role, a patriotic finale, or a piece of new choreography that asks them to reinvent themselves again. They do not complain. They do not posture. They work. They give us their best years, their discipline, their precision, their care. And if anything still resembles an American virtue, it is that.

As I sat there watching it from my floor seat, in my ball gown, diamonds and sapphires and gold catching the light every time I moved, I couldn’t help but feel the dissonance. The finale leaned heavily into George Balanchine’s Stars and Stripes, ultra-patriotic and unapologetically theatrical. Some critics later compared it to the Rockettes. Sitting there in the room, that comparison crossed my mind as well. The choreography veered Broadway, the music Gershwin-ish to the point of near caricature, almost Looney Tunes at moments in its insistence on American exuberance.

What made it land so strangely was not the dancing, which was executed with total professionalism, but the context. From that seat, dressed for ceremony, watching this hyper-stylized patriotism unfold, my mind went to friends of mine in Minneapolis, music industry friends who were afraid to get in their cars and leave their homes because of the political unrest there. The contrast was jarring. The finale did not feel grounded in the moment we are living in. It felt theatrical in a way that bordered on farce, like a satire of how Americans are seen celebrating themselves from the outside.

And yet, even as I registered that discomfort, I found myself thinking less about whether it “worked” and more about what it was doing. I’ve spent enough time in nonprofit arts spaces to understand the pressures at play. This is a company navigating funding requirements, donor expectations, and institutional survival. The finale may have been show-tune-y, even cheesy, but it was also positioned deliberately, placed after a program that had otherwise been stripped back, modern, minimal, and intellectually rigorous. In that contrast, the intent became clearer.

After the performance, the afterparty took on a different energy, one that felt earned. The dance floor filled completely, bodies packed in, jackets discarded, heels kicked off. There was a collective sense of release, as if everyone had let go at the same time. For the first time since the election cycle, it felt like the room was not segmented by politics, profession, or posture. People were simply together.

About an hour and a half in, just as that looseness settled in, the music cut. The Golden State Valkyries’ mascot, Violet, burst into the room with the team’s dance squad, launching into a full floor show. They danced to Too Short. Then E-40. It was abrupt, chaotic, and unmistakably Bay Area. Ballet patrons, dancers, donors, and friends folded into the moment without hesitation.

In a year marked by division, the moment felt like release rather than diversion.

There is always a moment at the end of the night when your car arrives and everything accelerates again. Dresses gathered in one hand, phones in the other, rushing down the grand staircase of City Hall. The valets in white coats begin to resemble coachmen. Waymos idle like driverless carriages, lined up and ready to take you home. It feels a little like Cinderella, dashing down the steps before the clock runs out. Before you turn back into a pumpkin, or in my case, a culture editor, running off into the night with the image intact just long enough to keep it.

I left the gala feeling something rare: steadiness. Not blind optimism, not denial, but confidence born of watching people do their work with clarity and care. Confidence that comes from seeing artists show up fully for one another, night after night, even when the conditions are imperfect. Even when the politics are messy. Even when the finale is complicated.

Especially then.

Because what endured was not the spectacle, but the labor beneath it. The discipline. The trust. The relationships built over years of shared rehearsal rooms, shared risks, shared belief in something worth protecting. In a moment when so much feels fragile, that kind of steadiness matters. It doesn’t announce itself or demand attention. It holds the room long after the lights come up.

Looking ahead, the San Francisco Ballet will open its full 2026 repertory with Eugene Onegin, running at the War Memorial Opera House from January 23 through February 1, 2026. This world premiere by resident choreographer Yuri Possokhov is a richly layered adaptation of Alexander Pushkin’s classic tale of love, regret, and the fragility of the heart, set against the twilight of imperial Russia and driven by big emotional stakes and intense dueling relationships. Performances include evening and matinee shows across the run, and tickets are available now through the San Francisco Ballet’s official box office and website, as well as trusted marketplaces such as SeatGeek and AXS.