I’m a queer person who attends a Christian church, though I hesitate to call myself a Christian because of the harm done in Christ’s name. This piece isn’t about changing anyone’s beliefs. It’s about how sacred love shapes the way I try to love others in secular life—because the “biblical values” I hold are rooted in love, dignity, and compassion.

For me, the Gospel—especially the teachings of Jesus—is less about doctrine and more about how we treat one another.

Called to Love

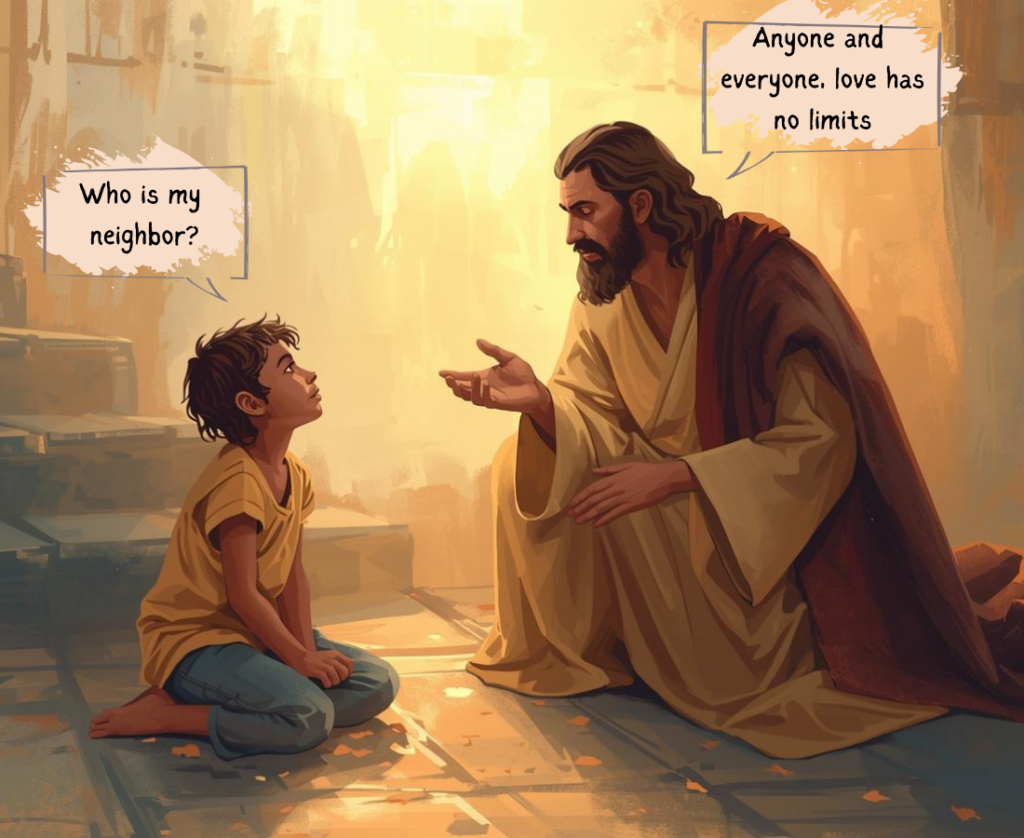

In Scripture, Jesus names the greatest commandment clearly: Love God with all your heart, soul, and mind. Then he adds, “And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself’” (Matthew 22:40). Love is supposed to be the clearest instruction God ever gave. Yet even in the Bible, people tried to narrow that command. In Luke’s version of the story, a teacher of the law asks Jesus, “Who is my neighbor?”—essentially asking where the obligation to love ends and who can be excluded.

Jesus answers with the parable of the Good Samaritan. A man is beaten and left for dead on the side of the road. Two religious leaders—people who would have claimed to uphold “biblical values”—walk past him without offering help. Then a Samaritan, a member of a despised and marginalized group, is the one who stops, tends to his wounds, and ensures his safety. When Jesus asks which person was a true neighbor, the answer is obvious: “The one who had mercy.” And Jesus responds, “Go and do likewise.”

The message is unmistakable: Our obligation to love does not end. It does not shrink to fit our comfort, our doctrine, or our fear. It expands toward whoever needs mercy.

Defining Love

If we’re going to talk about “biblical values,” then we have to be honest about what the Bible actually says love looks like. Scripture doesn’t leave this vague or symbolic; it gives a concrete description. In 1 Corinthians 13, love is patient and kind. It is not proud, not rude, not self‑seeking. It doesn’t insist on its own way. It protects, trusts, hopes, and endures. This is not the love that corrects people into conformity or polices their identities. It’s not the love that shames, excludes, or demands obedience as proof of worthiness.

This is a love that moves toward people, not away from them. A love that heals rather than harms. A love that refuses to weaponize itself. When someone claims to act out of “biblical values” but their actions are impatient, unkind, controlling, or cruel, then they are not practicing biblical love at all. They are practicing something else entirely—something Jesus never taught and never modeled.

Love is Not Religious

And here’s the part that matters for where we’re going next: Nothing about this description of love is exclusively religious. Patience, kindness, humility, mercy, protection, and care—These are not uniquely Christian virtues. They’re human ones. You don’t need a church or a creed to practice them. In fact, many queer people, many marginalized people, and many who’ve never stepped inside a sanctuary embody these qualities more faithfully than the institutions that claim to own them.

When Scripture describes love, it isn’t outlining a doctrine. It’s offering a way of moving through the world—a way of seeing others as worthy of dignity and compassion. That’s why I don’t treat the Gospel as a set of rules, but as a lens that shapes how I try to love people in everyday, secular life. Sacred love doesn’t belong to Christianity alone; it shows up wherever people choose empathy over fear, mercy over judgment, and care over control.

Sacred Love and Secular Love Are Not Rivals

This is where secular love enters the conversation: not as a rival to religious love, but as another expression of the same moral shape—the same expansive pattern of care that Jesus pointed to again and again.

When we look honestly at what love requires—patience, kindness, mercy, protection, humility—It becomes clear that both sacred and secular expressions of love point in the same direction. They may use different languages, different metaphors, different sources of authority, but the shape of the love is the same. It widens. It makes room. It refuses to treat anyone as disposable.

And if that’s true, then acceptance isn’t a modern invention or a political stance. It’s the natural outcome of love itself. You cannot practice patience while rejecting someone’s humanity. You cannot practice kindness while denying someone’s dignity. You cannot practice mercy while drawing boundaries around who deserves it. Whether it comes from Scripture or from shared human experience, real love—the kind that heals, protects, and refuses to harm—always moves toward acceptance.

This is why I believe sacred love and secular love are not opposites. They are parallel expressions of the same moral shape—a shape that refuses to harm, refuses to control, and refuses to exclude. Both forms of love call us toward the same truth: People deserve dignity, safety, and belonging simply because they are human.

Finding a Church Community that Practices Love

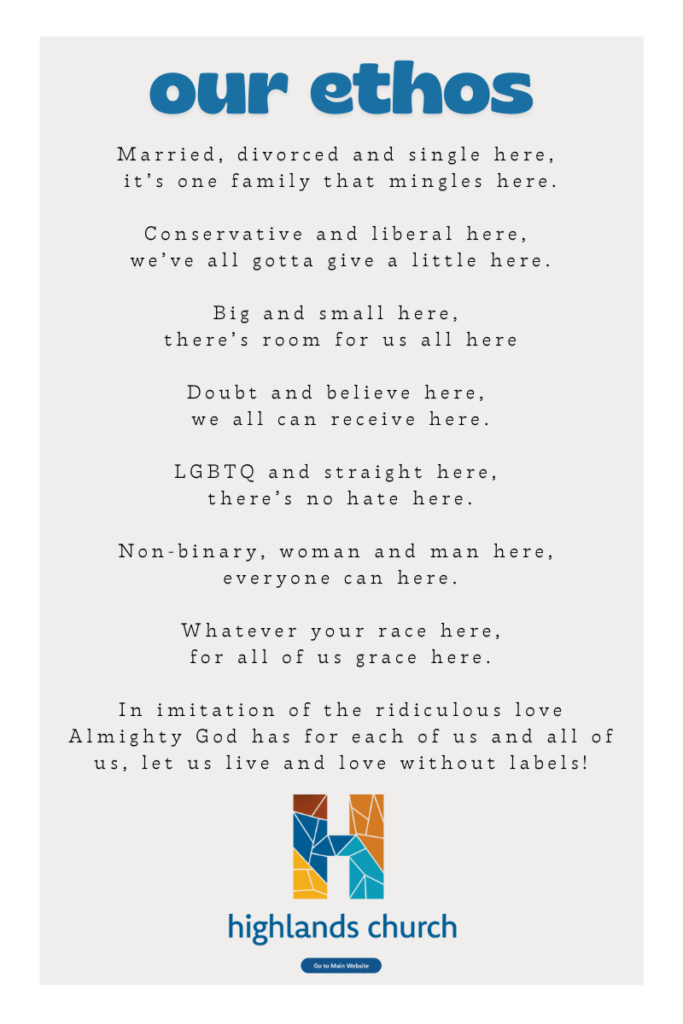

And this is where I find resonance with the ethos of Highlands Church Denver, a community that says plainly: “We are a place of acceptance and love for all people, without condition.” That ethos doesn’t erase the harm done elsewhere, and it doesn’t pretend the church has always lived up to its own teachings. But it does reflect the kind of love I see in Scripture—the kind that heals instead of wounds, welcomes instead of judges, and insists that every person is worthy of care.

At the end of the day, this isn’t about defending Christianity or critiquing it. It’s about reclaiming love from the people and systems that have twisted it into something unrecognizable. It’s about naming the truth that both sacred and secular expressions of love point us toward the same place: dignity, compassion, and belonging.

As a queer person who still finds meaning in parts of Scripture, I hold this tension every day. I know what it feels like to hesitate before using the word “Christian,” not because of Jesus, but because of the damage done under His name. And yet, I also know what it feels like to sit in a community where love is practiced instead of weaponized—where the teachings of Jesus are not used as a boundary, but as a bridge.

That’s why the ethos of my church matters to me. It’s not a slogan; it’s a compass. It reminds me that love is not something we gatekeep or ration. It’s something we practice, imperfectly but intentionally, in every direction we can. And it calls me back to the kind of love I want to embody in the world—a love that widens the circle, protects the vulnerable, and refuses to let fear decide who belongs.

In imitation of the ridiculous love Almighty God has for each of us and all of us, let us live and love without labels.

Graphics courtesy of the author and Highlands Church