Unsung Era: Forgotten Tales from the Golden Age of Gay

You’d be forgiven for thinking the Golden Age of Gay occurred in the late 20th Century. It’s a common narrative—LGBTQ rights originated after, and because of, the Stonewall Riots. It’s also wrong.

The Stonewall Riots remain a largely misunderstood pinprick of time within the greater chronology of queer history—one that, scholastically documented at least, stretches back more than 5,000 years.

Reality is, as usual, far more sticky.

Stonewall, perhaps for all the hype, gaywashing, factually-incorrect Hollywood blockbusters and misguided sentiments, was only the most visible—and visual—moment of the queer story.

We do ourselves a great disservice overshadowing our own incredible story by conflating Stonewall with myth, something other than what it was—common, unremarkable in an age of constant assault on marginalized communities, when lynchings were frequent and police raids often ended in blood baths.

In contrast to previous raids and other atrocities, like the little-known Upstairs Lounge Fire of 1973 or the legal police raids of the late 50s and early 60s, no one died. In fact, a number of celebrities and cultural icons were born. The Gay Liberation Front got queers to organize from coast to coast, but this was also not a first in queer history.

Was it important? Decisively so. Was it the genesis of us? Hardly.

Long before bricks were thrown, marches organized and rulings handed down, we can look back to an era more commonly associated with the excesses of capitalism and the advent of globalization.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were both decadent and … astonishingly queer. Move over, Oscar Wilde—There’s a lot of talent you opened the door for.

Many of the biggest names of the pre-war West, from titans of industry to tastemakers, were out(ish), proud, and thriving. Lasting contributions to Western culture, some of which continue to shape our present day, were made by fearless queers and their allies.

A few years after Wilde was jailed for sodomy in the U.K., and a century before Paris is Burning hit the mainstream, the first balls were held. Well-documented but little-known today, Harlem’s Hamilton Lodge was a very, very special place in 1869.

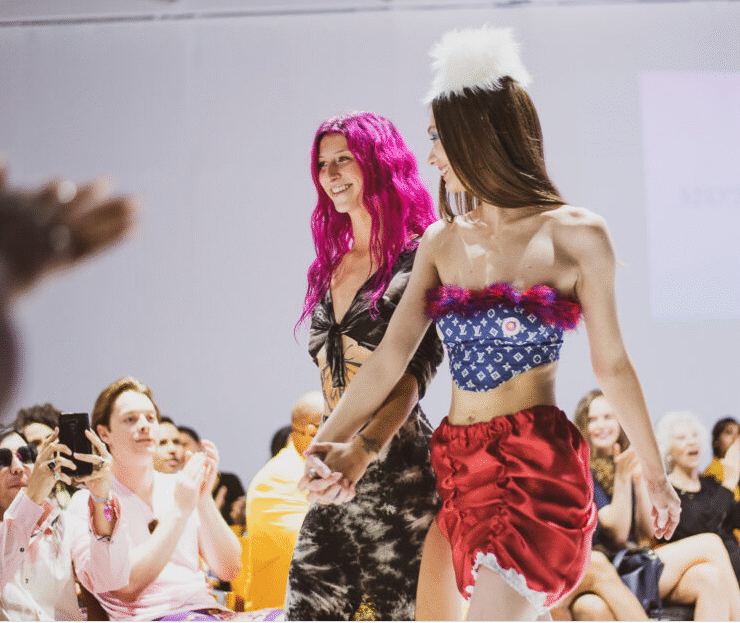

Originating as a safe space for BIPOC gay men to congregate, the drag balls grew in popularity across the country, as word spread about the Harlem Lodge events. The events were lavish affairs with “phenomenal male perverts” in high-end women’s clothing and wigs performing as women, as described by one moral-reform organization, The Committee of Fourteen.

The public took to calling them “Faggots Balls,” events which attracted a wide crossection of genders and sexes. Just as importantly, straight people—literaries and creatives—found themselves intoxicated by the all-night parties which were so different from typical heterosexual gatherings.

The drag balls were important, centralizing forces in an era with few protections and a shaky political landscape. Like minds from all walks of life safely met at the events, and with them came new ideas and artforms which rippled across the country and across time—ideas like queer advocacy.

By 1910, Emma Goldman became the first American queer rights activist. Even for a stated anarchist, her pro-queer views were considered radical for her time. She traveled the country giving talks on topics like birth control and homosexuality.

“It is a tragedy, I feel, that people of a different sexual type are caught in a world which shows so little understanding for homosexuals,” she wrote.

Many sympathized with her and the small, but growing, wave of queer support. Lesbian political activists and women’s activist organizations furthered the cause in their fight for suffrage, hard won in 1920.

That same decade, famously queer First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt fell in with that crowd, finding kindred in the unrestrained, sexually giddy atmosphere of Harlem and Greenwich Village—epicenter of the underground sexual and cultural revolution.

Concurrent to a life with her husband, the future President Franklin Roosevelt, she also maintained her own private throuple. For several years, she lived with lesbian activists Nan Cook and Marion Dickerman in a house far from the city. She later had an affair with a woman journalist on her husband’s campaign.

Back in Harlem, the daughter of America’s first Black, woman (self-made!) millionaire had her brush with the Bohemians. A’Lelia Walker, who never publicly stated her sexuality, was widely considered queer. Rich and libertine, she exemplified the opulent 1930s.

She became fast friends with gay icons of the day like Langston Hughes, Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Zora Neale Hurston—names which are taught widely in schools today with little mention of their queer identities.

Walker’s parties mirrored underground queer clubs across the nation, in places like Chicago and Los Angeles. While homosexuality and sodomy laws in the United States made queer identities illegal, underground drag balls and gay clubs could now be found in most cities.

“There were men and women, women and women, and men and men … Everyone did what they wanted to. They wanted to make love … it was marvelous,” lesbian activist Mabel Hampton, a guest at one of Walker’s parties, would recall in an interview given after the Netflix debut of Self Made.

The flourishing gay culture in the 1920s and 30s did a job it still does today—influence film, fashion, the visual and performing arts. Even after stricter laws were implemented in the decades after, the queers had sufficiently infiltrated the creative industries to maintain influence throughout legal oppression.

Largely, officially, public gay life in the West was a hushed affair, taking place behind closed doors and often in the loftiest bedrooms in government. While some countries moved to decriminalize homosexuality, many more were making it illegal, or worse: punishable by death.

European cities like London and Paris were rapidly urbanized and liberalized in their own ways. England, the nation that gave us Oscar Wilde and then jailed him in 1895, had a thriving underground gay community which sprawled into the upper echelons of English polite society.

Similarly, Berlin, Barcelona, and Prague had thriving, sometimes visible gay communities. All of these cities became cultural and financial meccas. Most hold that sway to this day.

The tragedy of more recent events, for example the state of Florida’s attack on the education system—is that queer history informs the rise of trends, mass-media, and mainstream culture as we know it today. If we only ever tell half-truths, or worse, no truths, the contribution of these incredible queers to our present day will be forgotten.

These are just a few of many on a very, very long list of queers who have contributed to our visibilty and influence today. Many have names. Many have been forgotten.

In the United States, an increasingly unsettled minority became a vocal moral majority, purging government agencies of homosexuals and reclassifying homosexuality as a mental illness. In cities across the country, laws were enacted which criminalized queerness officially.

In most cities, including Denver, law required that all patrons in a suspected queer bar have at least three articles of clothing on from their gender. “Transvestites” were beaten and dragged out of bars into the streets by uniformed officers.

Meantime, the narrative of the stereotypical gay man became that of a criminal sexual deviant. “All” gay men were, in the eyes of public opinion, pedophiles.

If all of this feels like a gauzy, distant dream with no resonance today, how did it all end? The spread of fascism abroad and authoritarian responses to crises domestically.

This Pride, it’s important to dust off this Golden Age of Gay and the lessons it’s handed down. Appreciate and celebrate our queer ancestors whose contributions have not faded but whose private lives and stories have.