The Art of Painting and Long-Distance Running with Eli Hill

“There’s a certain level of radical acceptance to welcoming discomfort. There’s going to be more difficulty existing as a transgender person, but to find community, to persevere with grace, is something that brings me so much pride.” – Eli Hill

We sat down with New York based artist, Eli Hill (he/they) for an interview about art, being trans, and long-distance running.

Where did you grow up and where are you now? How did you become interested in art?

I grew up in Port Huron, Michigan, which is outside of Detroit. Both of my parents were working class. My dad managed a dairy department out of Kroger, and my mom was a waitress then later a janitor for a mental health hospital. We briefly owned a bodega that we basically lived inside of.

No one in my family was artistic at all. My sister’s boyfriend, who was from New York, told us about Interlochen Center for the Arts, which was an arts high school in Michigan. I ended up going to high school there, mostly because I wanted to leave my hometown. The school asked me to pick a major, and I was like, “Well, I love making watercolors of Oprah; I guess I’ll be a visual artist.” During my time there, I started making sculpture, doing performance art, making fiber arts, and painting. This led me to study in New York at Cooper Union, where I started painting more seriously.

Can you describe your time as a student at Cooper Union? What about your time immediately after attending Cooper Union?

I went to Copper Union the last year that it was free. Attending Cooper Union was a very wacky experience. For example, I learned what a board of trustees was before I learned how to chop a piece of wood in the shop. I spent most of my first semester protesting the administration. Because of that, I had a very robust education, not just of art, but of being a part of an institution.

Cooper Union was amazing, and I had great mentors. It was also a very different climate at the time. I came out as nonbinary in 2016 towards the end of my time at Cooper Union. Part of the reason why I didn’t come out before that was because I saw how awfully other trans students were being treated. So, while Cooper Union was amazing, it was also of its time, and in that way, was not affirming.

I had a very rough time when I first left Cooper Union. I worked for an arts magazine, and I came out as trans in that space after I had interned and worked there for about a year. When I came out, I was not met with kindness. To this day, all of my articles for them are under my dead name.

How did you navigate coming out as nonbinary knowing that trans students were being mistreated? How did that time fuel your work or life today?

It was a mix of community and friendship that got me through it, but it was a very difficult time. I volunteer for Trans Lifeline now. One of the main reasons that I volunteer for them is that I have experienced very heightened states of depression and anxiety. This is largely due to stigma and oppression that I have experienced as it relates to my trans identity. Now I feel like I’m in a space where that doesn’t totally dictate my life.

It is really wonderful to talk to and be able to hold space for other people that are in a rough place. One of the main words that we use in Trans Lifeline is, resilience. Sometimes, I think as trans people, we don’t realize what an incredible trait or skill that is. It really is something that not everyone embodies as thoroughly or in such a beautiful way as we do.

Endurance and resilience are definitely core parts of my personality.

I can see those parts of your personality reflected in your artwork and long-distance running practices. There are also aspects of your work that are soft, vulnerable, and even radical. I would be curious to see how you might relate your practice to trans complexity and introspection.

There was a point in time where narratives around trans people were centered around trans death. Then it shifted and there was a pushback where instead narratives around trans people became about trans joy. From there, we became both joyful and resilient. When in all actuality, why are we now only joyful and resilient? Why can’t we be perceived and represented as holistic, whole people?

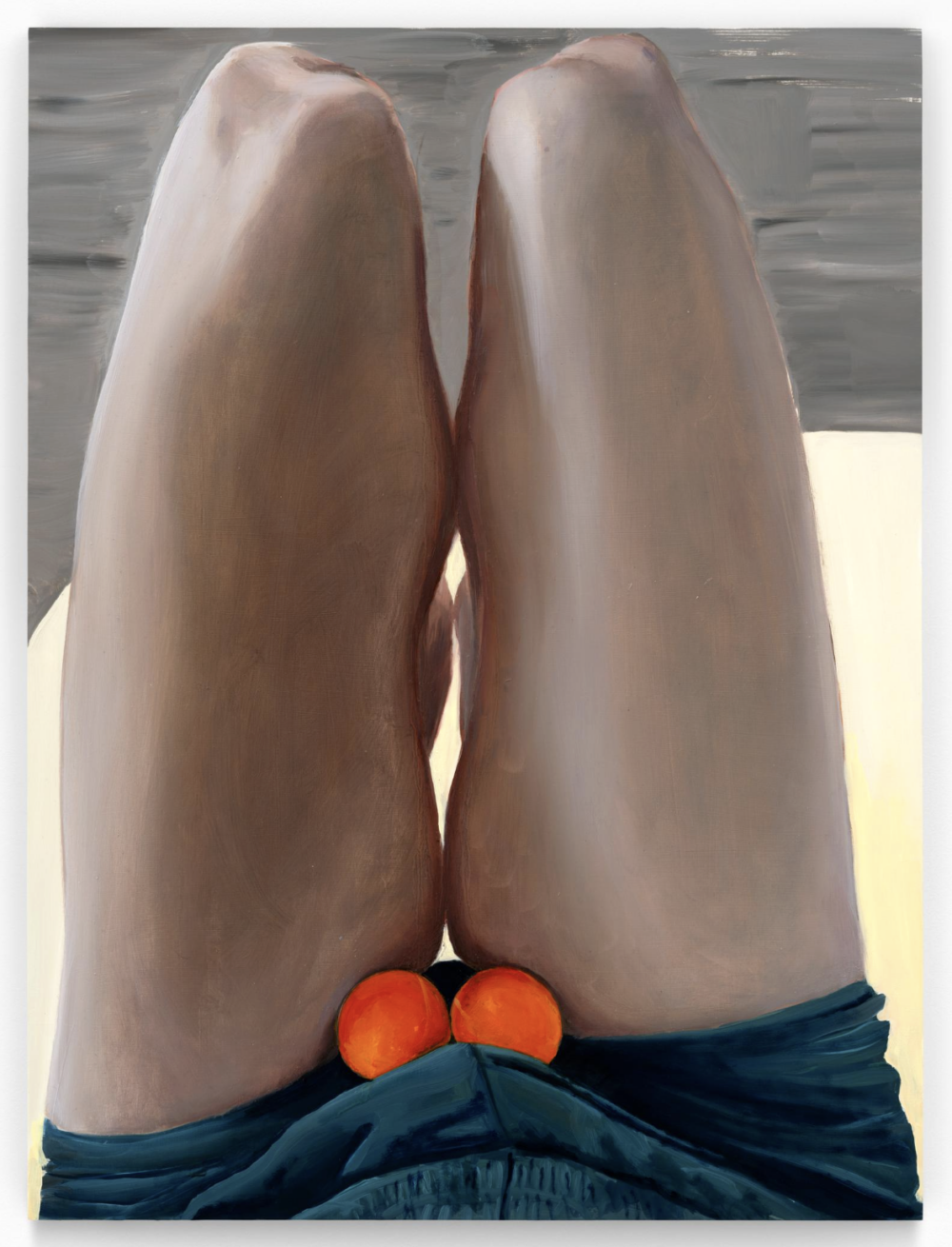

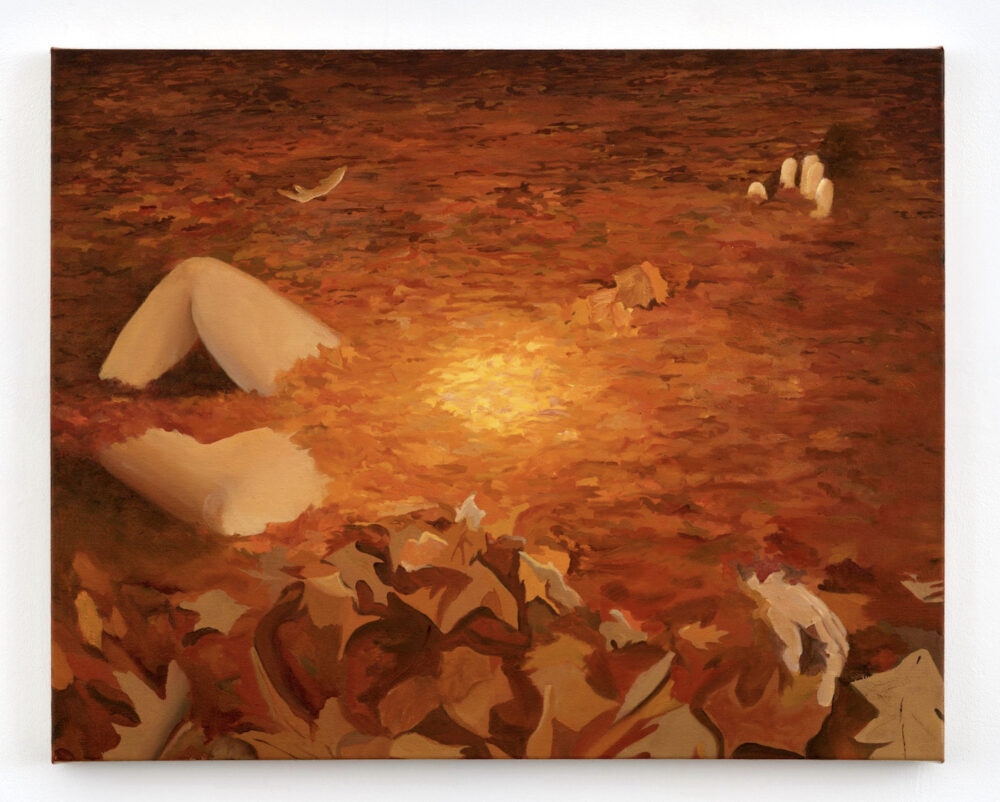

My last two bodies of work were very quiet paintings. They were mostly paintings of figures or of leaves in Forest Park, which is one of the parks that I train for runs in. I do trail runs there, and there’s also a track. In addition to that, I clean the trails as a volunteer.

Being in nature and being alone are things that bring me an actual sense of peace and calm. When I moved out to Ridgewood and found Forest Park, I didn’t even realize how much I had missed being near the woods and being in an actual forest. When I went to boarding school, the woods were all around me. I made artwork in the woods when I was a teenager.

When I am in a preserved forest, I think about how this ecosystem has persevered through living amongst the city. It has persevered because of the people who care for it; it’s so adaptable, quiet, and sturdy. Those are all traits that I feel deeply connected to. A lot of the paintings in my last body of work were trying almost to not talk about having to persevere. They were not talking about pain, joy, or extremes of trans experiences. Instead, they represented moments of solitude. An introspection of just being, within the context of the conversation of transness, felt radical to me in some way.

When you train for a run, where do you run to train and when? How does running relate to your studio practice?

I train for long-distance runs. I mainly train for half marathons. That’s my preferred distance. I started running to my studio during the longer portion of my last training period. I would run through Ridgewood, along the industrial area of Brooklyn by the water, over the bridge, around Lower Manhattan, and into my studio at World Trade Center. This run is about eight-and-a-half-miles.

By the time I arrived at my studio, I would be exhausted to a point where when I started painting, I wasn’t having rumination. I wasn’t thinking about what I was going to eat for lunch. I wasn’t thinking about if I needed to text someone. All I was thinking about was how tired my body was and what I was going to paint. Running is also a way to chill out my brain and get into my body in order to make artwork.

There are commonalities between running, painting, forest conservation, and volunteering to support transgender people. These activities all relate to radical embodiment and care. They are in direct opposition to disassociation and dysphoria. Can you talk about radical embodiment and transgender experiences? Also, how does disassociation related to transness in your lived experience?

Yeah, I realized that part of my disassociation was my over awareness of being perceived by others and guessing how I would be perceived by others. When you’re constantly perceiving your body through your interpretation of other’s perceptions, you’re unlikely to be in your body. For example, when I am deeply aware of how I might be perceived, I am less aware of what my body needs. Instead, I’m doing whatever I need to do to feel safe or to feel less anxious about being perceived.

For me, running and being in nature are both times where I’m either alone or with close friends. They are moments where I can let go of perception and just be. To me, that is part of what feels radical, especially because perception is so much of the trans experience. So many people have an opinion about if you are doing your gender wrong or right.

As a painter, part of my job is to perceive, to slow down, and to look. When I make paintings, I actively choose to make self-portraits because it’s a space where I get to perceive myself and nobody else is perceiving me. My self-portraits are an opportunity to craft my own narrative.

In addition to embodiment, there’s also an element of comfortability with discomfort in your running and creative practices. What kinds of recommendations would you give to readers who may be struggling with something uncomfortable?

Something that I witness a lot when teaching queer or trans undergraduate students is their reflex to avoid discomfort. I’ll often tell them, “You have to get comfortable with being uncomfortable.” It can sound like a cruel thing to say. In fact, one of my mentors told me that when I was in undergrad, and I was so angry. Now I deeply understand the importance of leaning into discomfort and see that this was a very caring thing to say.

There’s a certain level of radical acceptance to welcoming discomfort. There’s going to be more difficulty existing as a transgender person, but to find community, to persevere with grace, is something that brings me so much pride. To find deep community that understands you, to react to trauma with grace–not that we should have–is an amazing thing that I often see people in the trans community do.

I would recommend that people start embracing discomfort by engaging in simple acts of embodiment. Acts of mindfulness can build capacity for embodiment and in turn creates capacity to process discomfort through radical acceptance. Things like smelling the soap you’re using when you’re in the shower or giving yourself the space to breathe intentionally can be such radical acts. Especially if you’re being oppressed, your oppressor doesn’t want you to breathe, your oppressor doesn’t want you to slow down. A mantra I use is “you deserve the space to breathe.”

You literally deserve to slow down. We talk about taking up space physically, but what does it look like to take up space mentally for yourself, instead of just having other people’s voices in your mind?

What are you working on now, and what’s next for you?

The current body of work that I’m working on now is about the overlap between running and meditation. Also, bugs have been coming up a lot for me in this body of work.

I think meditation has shown up in a couple of different ways in these paintings. I wanted to almost try a Zen way of painting by painting every blade of grass. You can see this approach in the painting pictured above.

Follow Eli Hill’s work on Instagram @elielielihill or check out his website at elihill.net.