[Now Playing] Tanya Sarracho’s Fade Goes Beyond Stereotypes

Paul Bindel loves food preservation, poetry, and theatre. He lives…

Stereotypes are an easy way to negotiate the world — a shorthand guide that can comfortably categorize any human, from the bearded brown man in an airport line, to the single woman with a short haircut who loves to ride Harleys.

But stereotypes aren’t real and, like other forms of assumption, they’re efficient at preventing authentic relationships from forming. Not that folks should be intimately connected with every stranger on the street, but that it’s a lot easier to advocate for the Great Wall beside the Rio Grande when you’ve never met any first generation migrants or their Dreamer children.

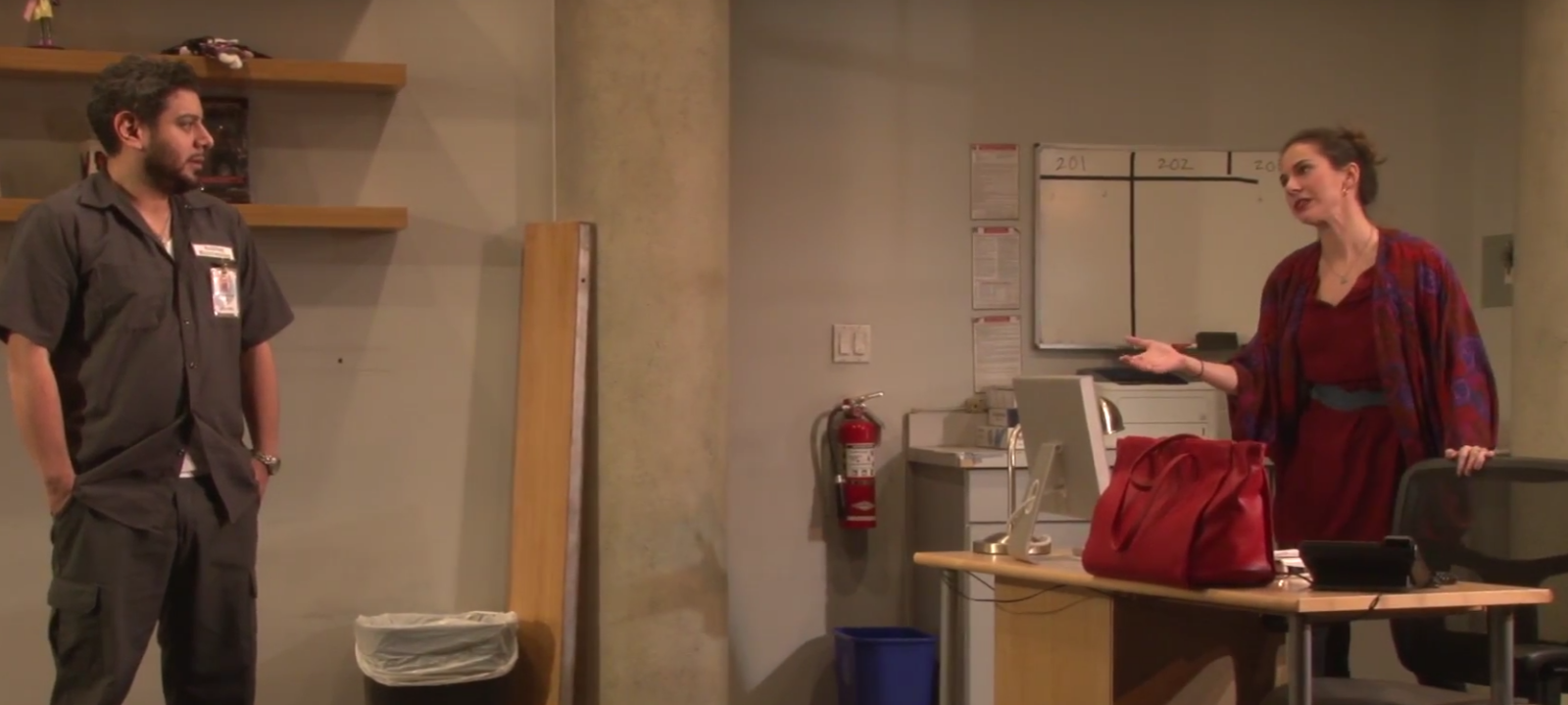

The Denver Center’s production of Fade, directed by Jerry Ruiz, begins in Spanish and in stereotypes, as television writer Lucia (Mariana Fernández) directs the janitor Abel (Eddie Martinez) to help her set up her new office (a brilliantly worn Ikea set designed by Timothy R. Mackabee). When Abel finally speaks — and in English — Lucia must backpedal a bit for assuming that he could only understand their mother tongue.

Fade is a smart play that dives into racial representation in the media while also exploring the complicated ways people of color relate to each other within white-dominated society. Tanya Saracho is no stranger to working within a white media landscape, calling herself “a playwright who writes for television,” and OUT FRONT readers have likely seen her work on Looking, Girls, Hung, Devious Maids, and How to Get Away with Murder.

Lucia has also been brought to work on a TV shows because they feature Latino characters, but she faces a battle convincing her co-writers to move beyond the “Ay! Dios mio!” stereotypes. Lonely in a new city and working long hours, she swaps stories with Abel — partly because of their shared Latino heritage — and an unusual friendship emerges. The two embody and also defy some of the stereotypes associated with Latinos: He grew up in East L.A., joined the Marines, and spent some time in prison; she, like Saracho, grew in up in “El D.F.,” moved to Chicago, and then was hired to work in television in L.A.

When Lucia waxes nostalgically about the street tacos of Mexico that her childhood maid used to bring her, Abel is quick to call her out as a “fresa.”

“You had a maid?” he asks.

“Well, that’s a thing now in Mexico. Even maids have maids.”

Lucia’s refusal to acknowledge her class difference is part of what makes her relationship to Abel possible, and her career ambitions threaten to end it. The truth is that, in spite of class, she and Abel have more in common than not — her boss and coworkers see her as “the Hispanic hire” rather than a talented writer.

The play’s devastating ending is clear from almost the beginning, but its tension lies in how it defers this ending with the alluring promise of class politics and with a lot of great jokes. Neither Fernández nor Martinez miss a beat, keeping the scenes punchy and lively, something that can be hard to pull off in a two-person play. The characters transcend stereotypes, and we want them to form a friendship and a politics that leads them both to a better life. Indeed, Saracho told Chicago Magazine how, in an early television writing job, her friendship with Latino television network janitors led her to “almost [go] on strike” to demand they receive benefits. Maybe that relationship is not stereotypical enough for television or stage.

Fade runs at the Denver Center for Performing Arts until March 13.

What's Your Reaction?

Paul Bindel loves food preservation, poetry, and theatre. He lives in and writes from a housing cooperative in Capitol Hill.